Succeeding @ Youth Sports

In his best-selling book “Outliers”, Author Malcolm Gladwell states, “10,000 hours is the magic number of greatness.” In other words, if you practice 10,000 hours, you could be great…or maybe not. According to a recent study, “Practice Does Not Necessarily Make Perfect”. Instead, “greatness” can be attributed to a variety of factors. In sports, we only have to work backwards from what’s measured at the highest levels to see that ‘practice’ is just one component in an equation that also includes technical, tactical, physical, and psychological inputs, or TTPP for short.

If your athlete goes far enough in sports, you will notice that player assessment (forms and software), elite training programs, professional player development, recruiters, academies, scouts, coach training, and more are all leveraging holistic formulas that include TTPP.

So what should the parents of a young athlete focus on?

I am not an expert. Three of our kids graduated as varsity athletes; our youngest plays club soccer at a high level; I have coached soccer for many years; and as an entrepreneur, I have invested ~2,000 hours researching venture opportunities in youth sports.

I have given a lot of thought to succeeding at youth sports: what it looks like, how to obtain it, and why we should care.

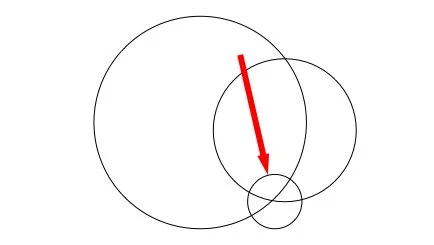

In the early years, adults are obviously part of the equation. If you (the adult) and your athlete invest 3,000 hours into youth sports you can preserve three overlapping probabilities for success (see red arrow).

High probability (big circle): your athlete will become confident, outgoing, responsible, a team player, meet long-term friends, and make a lifetime commitment to health and fitness.

Reasonable probability (medium circle): your athlete will become a varsity athlete, a collegiate athlete, participate in club sports, and perhaps coach as a parent.

Extremely low probability (small circle): your athlete will be awarded a D1 scholarship, become a pro, and/or coach professionally.

It’s unpredictable, but if you and your athlete invest 3,000 hours filling the technical, tactical, physical, and psychological [TTPP] buckets, all outcomes — however remote — are possible.

Think of the first 3,000 hours as nearly a third of the way to the 10,000 hours needed to achieve mastery. The amount of hours invested per week ramps up with age. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all schedule to follow. Some kids reach mastery by age twenty, and some need five or six additional years. Accelerated investment [in a sport] doesn’t seem to be a surefire recipe. Who hasn’t seen a fast-starter (technical) that’s either lost (tactical), repeatedly injured (physical), and/or unhappy (psychological)? All of the TTPP buckets have to be filled.

In invasion sports (e.g.: soccer, hockey, basketball, lacrosse, football, etc.) where one side is always invading or defending territory, filling the TTPP buckets includes, but is not limited to:

T- Technical: The athlete is acquiring the 1v1, handling, and scoring confidence needed to assume responsibility for predominantly enabling (when attacking) or preventing (when defending) FORWARD movement of the ball or puck; versus relying upon a teammate to do it. (Eventually, someone has to move ‘it’ forward.)

T- Tactical: The athlete is acquiring the right-place-right-time situational knowledge needed to reliably participate in, or prevent, an invasion.

P — Physical: The athlete is acquiring [experiencing] an understanding of how nutrition, rest, and age-appropriate training for strength, stamina, agility, balance, coordination, and speed are all interconnected and essential to competing and winning.

P — Psychological: The athlete is learning how to embrace failure, how to process criticism, how to live in the present, how to visualize success, that succeeding in sports requires a ‘marathoner’ not a ‘sprinter’, and that the [bucket filling] journey…is the reward. Link

Google “technical tactical physical psychological” to learn more.

Note: Experts strongly suggest that kids “should not take part in organized sports activities for more hours per week than their age. For example: a twelve-year-old athlete should not participate in more than twelve hours per week of organized sport.”

The psychological bucket — the smiles bucket — is the hardest to fill. Motivating a child to happily invest 3,000 hours is the most formidable job in youth sports. Most kids quit before they become teenagers. Eventually, everyone has to self-motivate, but until early adulthood, parents and coaches play a big role in filling and [unfortunately] draining the smiles bucket.

The graphic above depicts a scenario that is all too common: technical, tactical, and physical buckets are filling, while the psychological bucket is empty…and your athlete wants to quit. How come? There’s a parent that thinks he’s building a pro, or a coach that thinks she’s launching a career, and one or both of them are fun crushing zombies.

Fun has to be the organizing idea…full stop/period. It’s amazing how many parents fail to put a foundation of fun under their athlete’s entire youth sports experience. It’s certainly not easy to position, plan, and execute every action and activity as fun. Nevertheless, everything and anything, including your advice, coaching, prodding, and feedback that’s not underpinned with an intention to fill the smiles bucket…drains it. I’ve done this. We all do it. This is easy to fix.

Begin by teaching your athlete what future fun looks like…and how to earn it.

Humans are transactional. I do X, and then I get Y. (I go to the dentist; I get a toy.) As kids and parents transact, a fun-trust account either fills or depletes. Parents create a fun-trust surplus when they consistently and reliably deliver the fun/joy/happiness they promised or implied. With a fun-trust surplus, it’s easier to pitch complex transactions that include [distant] future gratification.

In other words, parents dedicated to delivering fun in the early years and judiciously thereafter will succeed at pitching hard work, practice, patience, perseverance, and even setbacks as pathways to future fun. Conversely, no-fun parents with fun-trust deficits can’t make the same pitch. Everything about sports can be positioned and organized as either fun or as a pathway to fun.

Note: Competency builds confidence. The only way to build competency is to keep playing. The only way to keep them playing is to keep it fun. Until it’s a job, kids PLAY sports. Suggested Ted Talk

Along the way to 3,000 hours, you will see amazing young athletes that have incredible technical skills and/or advanced physical capabilities; they will seem so talented and so advanced that you may be tempted to drop out of the race. Don’t. Bigger, faster, stronger, or two years of extra experience are not reliable markers for future success. In fact, if anyone in the world could reliably predict which athletes at twelve will be successful at twenty-two, they would be wildly wealthy. Early selection is a myth; late bloomers are common; and all of the TTPP buckets have to be filled.

If you are a competitive person that’s wondering at this point, how to win, how to beat the system, and how to arrive at the end of the journey on top. Here are two observations:

First, ‘winners’ seem to simply win the war of attrition. As noted above, most kids quit, including most of the ‘future hall-of-famers’ that have been identified early on by so-called ‘experts’. Every athlete that plays a sport for fifteen to twenty years wins.

Second, overachievers have one thing in common: they’re smart and deliberate goal setters.

So, here’s my formula: During the first 3,000 hours, preserve all of your athlete’s options by filling all four of the TTPP buckets; always make it fun; ignore all the hype pertaining to young superstars…even when they’re yours; and guide the entire process via goals that are great, granular, gritty, and guided.

Goals — Activities and actions are undertaken with SMART goals in mind. Goals are essential. Work with your athlete to set weekly, monthly, season, and longer-term goals. Every two weeks, take ten minutes to review progress.

Great — Activities and actions are intended to be [great] fun, or a pathway to future fun. Especially in the early years, if it’s not fun, you’re draining the smiles bucket.

Granular — Deconstruct big picture goals such as ‘get better’ or ‘score more’ into granular goals (and routines) that add up to something bigger. Granular example: three times a week, kick with my left foot, from the right side of a small target that is twenty feet away, and strike the target ten times out of one-hundred attempts; adjust upward as the goal is met.

Grit — Choose activities and actions where initial failure is probable, a bit of agony is inevitable, and hard work is required; doing so builds grit. A good example of the intersection of grit and fun is when kids compete against older siblings.

Guided — Use highly qualified coaches and instructors to make granular adjustments, and to obtain continuous advice and feedback. (Parents are rarely qualified to do this.)